Breast and Skin Cancer Connection: Is There a Link?

- Foreword

- Part One: Two Common Cancers, One Patient

- Part Two: Breast Cancer After Melanoma — What the Data Says

- Part Three: Melanoma After Breast Cancer — Uncovering a Subtle Pattern

- Part Four: Shared Genetic and Familial Risk

- Part Five: Melanoma in the Breast — Understanding Rare Presentations

- Part Six: Hormones, Immunity, and the Microenvironment

- Part Seven: Screening, Surveillance, and Survivorship

- Part Nine: Frequently Asked Questions

- Closing Thoughts

Foreword

If you’ve been through cancer once, your mind doesn’t return to baseline. Every follow-up test, every lab result, every new symptom — it carries a different weight. So when you hear that some cancers may be linked — like breast cancer and melanoma — it’s not just an academic question. It’s personal. Could that second diagnosis be waiting in the wings?

That’s why this question keeps surfacing: Is there a connection between breast cancer and melanoma? Are people who’ve had one more likely to develop the other? Is there a shared cause, a common gene, or just statistical coincidence?

You may have stumbled on studies or forum posts suggesting a link — maybe you know someone who’s had both. You might have seen the term “melanoma breast cancer” and wondered what it actually means. The answers, like most things in oncology, are layered. And this article is here to untangle them, carefully, without turning patterns into panic.

We’ll look at the epidemiology — who gets both cancers, how often, and in what order. We’ll talk about genetics, particularly overlapping mutations like BRCA2, CDKN2A, and BAP1, that may explain why some families or individuals face both risks. We’ll clarify the rare situations where melanoma shows up in the breast itself, and how that differs from having two distinct cancers. We’ll dig into treatment histories, radiation effects, immune shifts, and hormonal pathways that might connect these two diseases biologically.

But we’ll also address something just as important: how patients live with that uncertainty. Survivors of one cancer often live with a heightened sense of vigilance — and that vigilance is justified. Still, it needs grounding. Not every recurrence is a new cancer. Not every cancer leads to another. But when links do exist, understanding them early gives people — and their doctors — a real chance to act.

So whether you’re a breast cancer survivor worried about your skin, a melanoma survivor curious about your breast health, or someone just trying to understand why these two seemingly unrelated cancers keep appearing in the same headlines — you’re in the right place.

Let’s start with the basic question: how often do breast cancer and melanoma show up in the same person — and what does that actually mean?

Part One: Two Common Cancers, One Patient

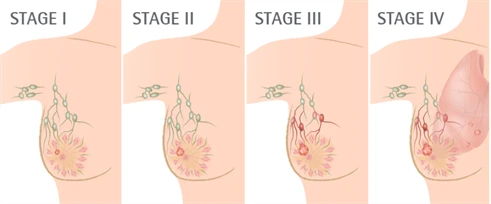

Individually, breast cancer and melanoma are among the most commonly diagnosed cancers in the world. Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women globally. Melanoma, while far less common overall, is the deadliest of the skin cancers and one of the fastest-rising among younger adults. Both have strong public awareness, high screening visibility, and long survivorship curves.

So when they occur in the same person, it’s natural to ask: is that a meaningful pattern — or just coincidence?

Statistically speaking, a person who survives one common cancer and lives for decades has a higher baseline chance of developing another. That’s true for many combinations — breast and colon, prostate and skin, lymphoma and thyroid. Some of that overlap comes simply from age and exposure. Cancer risk increases with time. The longer a person lives after a diagnosis, the greater the statistical likelihood of encountering a second malignancy — whether related or not.

But when researchers look more closely at breast cancer and melanoma, something more specific appears. These two cancers co-occur more often than expected by chance, especially in women, and especially in long-term survivors. One study of U.S. cancer registries showed that melanoma survivors had a significantly higher risk of developing breast cancer, and breast cancer survivors had a modest but real increase in melanoma incidence, even after adjusting for confounders like age, race, and treatment exposure.

This doesn’t mean one cancer causes the other. It doesn’t mean every breast cancer survivor will get melanoma, or that every melanoma survivor needs a mammogram tomorrow. But it does suggest that there’s more to investigate — whether in shared genetics, immune pathways, hormonal factors, or even systemic responses to treatment. And it changes how doctors might think about screening and long-term follow-up, especially in patients with no obvious risk factors.

The connection is also reinforced by patient experience. Many people who’ve survived one of these cancers feel a sharper awareness of their body, and a lower threshold for noticing changes — a new mole, a subtle skin shift, a lump that wouldn’t have prompted concern before. This vigilance leads to earlier diagnosis — and in some cases, catches that second cancer before it spreads.

So the question isn’t whether it’s possible to get both. It clearly is. The better question is: when it happens, is it just bad luck — or a meaningful signal? That’s what the next sections will explore: what the data says about breast cancer risk after melanoma, and vice versa, and how those risks are starting to shape real decisions about monitoring and prevention.

Part Two: Breast Cancer After Melanoma — What the Data Says

For a long time, follow-up care after melanoma was focused almost entirely on the skin. Regular full-body exams. Lymph node checks. Patient education on sun avoidance and mole monitoring. And for many patients, that was the end of it — no one mentioned mammograms, breast density, or hormonal risk profiles. Melanoma was a skin disease, and breast cancer was something else entirely.

But that’s changed. As researchers began to follow melanoma survivors over decades, new patterns emerged. Among women treated for melanoma, rates of subsequent breast cancer were higher than expected, even after adjusting for age and routine screening. The numbers weren’t dramatic — not every survivor faces double risk — but the trend held across multiple datasets.

One study published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention followed over 12,000 female melanoma survivors and found a statistically significant increase in breast cancer incidence, especially among women under 50. Another analysis of SEER registry data found that women with melanoma had a 14–20% higher risk of developing breast cancer compared to the general population. While that’s not enough to suggest a direct causal link, it is enough to change how many clinicians think about secondary prevention.

Why Might Melanoma Increase Breast Cancer Risk?

There’s no single explanation. Instead, researchers point to several biological and behavioral factors that may interact.

First, there’s the role of shared genetics — something we’ll explore more fully in Part Four. Certain inherited mutations, particularly in CDKN2A or BRCA2, may predispose individuals to both cancers. These mutations don’t act like switches; they increase risk in subtle, cumulative ways — altering how cells repair DNA damage or respond to hormonal signaling.

Second, there’s the idea of shared immune modulation. Melanoma is a cancer that often arises in the setting of immune dysregulation — where T-cell surveillance fails, or chronic inflammation primes the microenvironment. Breast cancer, particularly triple-negative subtypes, may also be influenced by immune evasion mechanisms. It’s possible that people predisposed to one immune-sensitive malignancy may be more vulnerable to others.

Third, there’s the question of exposure and detection. Melanoma survivors tend to have more frequent clinical encounters — dermatology visits, oncology reviews, lab tests. This increased medical surveillance may lead to earlier detection of other cancers, including breast cancer, simply because people are being watched more closely. In other words, the link may be partly observational, driven by access and attention rather than biology alone.

Finally, some researchers speculate about hormonal influence. Estrogen affects both melanocytes and breast tissue, and although the evidence is limited, there may be a connection between estrogen signaling and melanoma progression, especially in women. This area remains underexplored but continues to generate interest in oncologic research.

What Does This Mean for Screening?

For most melanoma survivors, breast cancer screening follows standard guidelines: annual or biennial mammograms starting at age 40–50, depending on personal and family history. But for those with early-onset melanoma, strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer, or genetic markers of elevated risk, screening may start earlier or happen more frequently.

Some specialists now recommend that women under 50 with a history of melanoma — especially if the melanoma was aggressive, or if there’s a family history of other cancers — be referred for risk assessment and possible genetic counseling. Not because melanoma causes breast cancer, but because the two together may reflect underlying genetic predisposition that calls for more careful monitoring.

Having one cancer changes the stakes. And for melanoma survivors, that includes thinking beyond the skin. Breast health becomes part of the long-term care conversation — not because the risk is overwhelming, but because it’s measurable, actionable, and increasingly well-documented.

Part Three: Melanoma After Breast Cancer — Uncovering a Subtle Pattern

When breast cancer comes first, melanoma often isn’t on the list of expected complications. Patients are monitored for recurrence, for metastasis, for lymphedema or cardiotoxicity — but rarely for skin cancer. And yet, several long-term studies have shown a small but persistent increase in melanoma risk among breast cancer survivors, even years after treatment.

This isn’t an epidemic-level rise. The absolute risk remains low. But the signal appears consistently enough — across U.S., Australian, and Scandinavian cohort studies — that oncologists have started asking why.

What the Data Shows

Large registry-based studies have observed a 10–30% increased risk of melanoma in women who have previously been treated for breast cancer. The elevated risk tends to emerge several years after the initial diagnosis, often during or after long-term follow-up. This makes sense — most breast cancer patients are watched closely for five years or more, giving researchers a window into what happens long after remission.

The association is stronger among women who were younger at the time of breast cancer diagnosis, and in some studies, among those who received radiation therapy, especially to the upper chest or axilla.

But even in patients who received no radiation and had no known genetic mutations, the pattern occasionally appears — suggesting that surveillance bias alone doesn’t explain it.

Possible Mechanisms: What Might Drive the Link?

As with melanoma-first cases, no single mechanism explains this pattern. But a few possibilities keep coming up:

Radiation exposure is the most commonly cited factor. Women who receive radiation therapy for breast cancer — particularly older techniques with broader fields — may experience incidental radiation to the nearby skin of the chest wall, neck, or upper back. While modern equipment minimizes this, cumulative UV exposure plus localized radiation may accelerate changes in melanocytes, especially in those with light skin or pre-existing moles.

Immunomodulation also plays a role. Some breast cancer treatments — including certain chemotherapies and long-term hormonal suppression — affect immune regulation. The immune system’s ability to surveil and destroy emerging tumor cells may be altered, leaving room for other cancers, including melanoma, to develop later.

Then there’s the possibility of shared genetic vulnerability. While BRCA mutations are most famous for breast and ovarian cancer risk, some studies have found mild elevations in melanoma risk among BRCA2 carriers. Other genes, like BAP1, CDKN2A, or mismatch repair mutations, may predispose to both cancers through broader pathways involving cell cycle regulation and DNA repair.

Finally, enhanced surveillance can’t be ruled out. Breast cancer survivors often undergo regular skin exams as part of survivorship protocols — especially those with fair skin or a family history of melanoma. This may partly explain the higher detection rate. But again, surveillance bias alone doesn’t account for the entire effect.

Should Breast Cancer Survivors Be Screened for Melanoma?

Currently, there are no formal guidelines recommending skin cancer screening in all breast cancer survivors. But many oncologists — especially dermatology-oncology teams — now recommend annual full-body skin checks for patients with additional risk factors:

- History of tanning bed use or severe sunburns

- Fair skin, freckles, or multiple atypical moles

- Family history of melanoma

- Personal history of radiation to the chest wall or axilla

Even in the absence of these factors, increased awareness and self-monitoring is advised. Patients are encouraged to track new or changing moles and to report any evolving skin lesions, particularly near the site of radiation fields.

Melanoma after breast cancer may be rare — but it’s not random. And while we may not yet fully understand the biological links, the pattern is real enough to justify vigilance. It’s not about alarm. It’s about anticipating the long arc of survivorship, and meeting it with information rather than surprise.

Part Four: Shared Genetic and Familial Risk

Most cancers aren’t inherited. But a small percentage — maybe 5% to 10% — are part of a heritable cancer syndrome, where specific gene mutations passed through families lead to earlier onset, multiple primaries, or unusual cancer pairings. These mutations don’t cause cancer outright, but they tip the balance: lowering the body’s defenses against DNA damage, or disrupting how cells regulate growth and repair.

That’s where the link between breast cancer and melanoma begins to sharpen. When both cancers appear in the same patient — or in a family with multiple early-onset cases — doctors often start to consider underlying germline mutations that might explain the overlap.

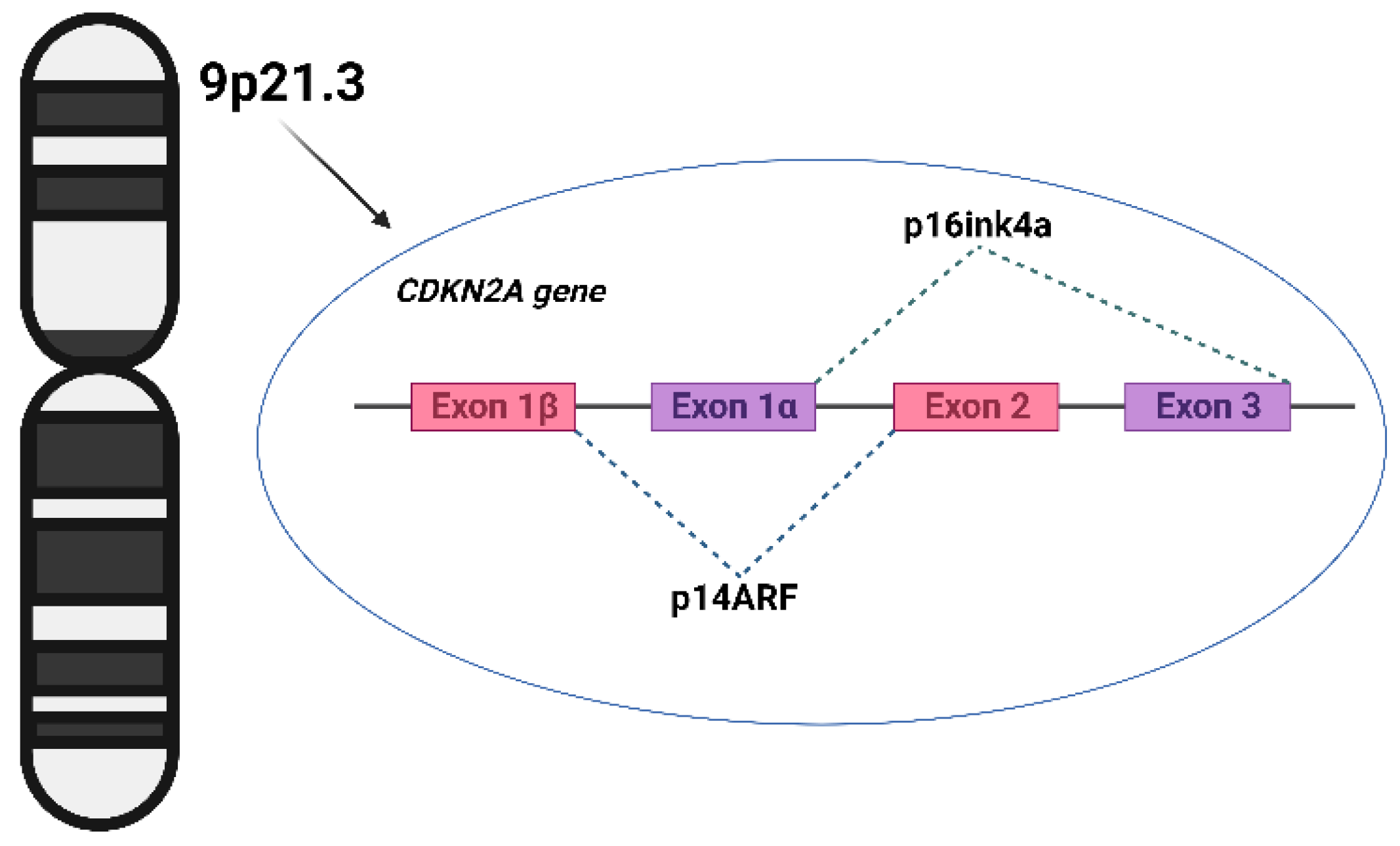

CDKN2A: A Melanoma Gene with a Broader Reach

The most closely studied melanoma-predisposing gene is CDKN2A, which encodes proteins involved in cell cycle control. Mutations in this gene are most often found in families with multiple melanomas across generations, and sometimes pancreatic cancer.

But CDKN2A mutations have also been detected in individuals with both melanoma and breast cancer, suggesting that the gene’s reach may be broader than previously thought. It’s not conclusive — the association is still being explored — but it supports a growing view that melanoma genes may intersect with breast cancer risk in certain contexts, especially when family history is strong and diagnoses occur early in life.

BRCA2: Better Known, but Still Not Fully Mapped

Most people associate BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with breast and ovarian cancer. These genes are crucial to DNA repair, and mutations can dramatically increase a person’s lifetime risk of developing breast cancer, particularly in younger women.

What’s less well known is that BRCA2 mutations may also modestly increase melanoma risk, especially ocular melanoma and cutaneous melanoma in men. The absolute risk remains low, and many carriers never develop skin cancer. But in families where both breast and melanoma cases cluster — especially at young ages — BRCA2 testing may be warranted.

BAP1 and Other Less Common Syndromes

Another gene drawing attention is BAP1, which is linked to BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome. People with BAP1 mutations may develop multiple cancers across their lifetime, including:

- Uveal melanoma (a rare form of eye melanoma)

- Cutaneous melanoma

- Mesothelioma

- Renal cell carcinoma

- Occasionally breast cancer

Though rare, BAP1 syndrome highlights the importance of thinking beyond common mutations. When patients present with multiple early-onset cancers, or unusual tumor combinations, broader genetic panels may reveal unexpected connections.

Other potential links — involving ATM, CHEK2, TP53, and mismatch repair genes (Lynch syndrome) — remain under study. Some of these genes affect both DNA repair and immune response, making them biologically plausible candidates for shared cancer risk. But most are not yet used to explain routine melanoma-breast cancer co-occurrence unless strong family history is present.

When Is Genetic Counseling Warranted?

Genetic testing isn’t appropriate for everyone, and it isn’t something most people need after just one cancer diagnosis. But in some situations, the combination of personal and family history suggests a deeper inherited vulnerability that deserves closer evaluation. For instance, if a person has experienced both melanoma and breast cancer — especially before the age of 50 — that’s a strong signal to consider a genetic referral. The same goes for families where multiple individuals have had one or both of these cancers across generations, particularly if those diagnoses came early or appeared in clusters.

Rare tumors can also shift the calculus. A history of uveal melanoma or unusually aggressive breast cancers, like bilateral tumors diagnosed before menopause, may reflect a high-risk mutation that standard panels would miss. Ancestry matters too. Individuals with Ashkenazi Jewish heritage, for example, carry a higher baseline likelihood of BRCA mutations, which have been implicated — at least modestly — in melanoma risk as well.

In these cases, a consultation with a genetics specialist can clarify whether testing makes sense, and if so, which panel is most informative. The goal isn’t just to understand one patient’s risks, but to guide screening decisions across a wider family network — including siblings, children, and extended relatives who might unknowingly carry the same mutation.

Understanding your genetic risk doesn’t mean knowing your fate. It means having a map. And for patients with both breast cancer and melanoma — or a family history that suggests more than coincidence — that map can shape everything from surveillance schedules to preventive strategies.

Part Five: Melanoma in the Breast — Understanding Rare Presentations

The phrase “melanoma breast cancer” is often misunderstood. Patients come across it in medical notes or online searches and assume it refers to a hybrid — some rare cancer that combines characteristics of both. But medically speaking, that’s not what it means. What it almost always describes is either melanoma that has metastasized to the breast, or in extremely rare cases, primary melanoma of the breast skin or tissue. Understanding the difference matters, because the diagnosis — and the treatment that follows — hinges on which one is actually present.

When Melanoma Metastasizes to the Breast

Melanoma has a reputation for wandering. Once it escapes the skin and enters the lymphatic or blood systems, it can travel widely — to the lungs, liver, brain, bone, and, more rarely, the breast. While the breast is not a common site of melanoma metastasis, it has been documented in case reports and small series, usually in patients with a known history of advanced-stage melanoma.

When this happens, it often presents as a firm, painless lump, sometimes indistinguishable from a primary breast tumor on physical exam. Imaging studies — mammograms, ultrasounds, or MRIs — might pick it up, but they can’t determine origin. That requires a biopsy, and when the pathology report shows markers typical of melanoma (such as S-100, HMB-45, or Melan-A), the diagnosis shifts. What looked like breast cancer turns out to be a melanoma recurrence in a new location.

Treatment, in these cases, follows melanoma protocols — not breast cancer guidelines. Systemic therapy becomes the focus, not local excision or hormonal modulation. And because melanoma in the breast usually indicates widespread disease, oncologists typically order full-body imaging to assess the extent of metastasis before deciding on the next step.

What About Primary Melanoma of the Breast?

Even more rarely, melanoma can arise de novo in the breast — typically in the skin overlying the breast, but in some reported cases, within the nipple-areolar complex or subcutaneous tissue. These cases are exceedingly uncommon, and often misdiagnosed at first. Unlike more typical melanomas on the arm, back, or face, pigmented lesions on the breast may be assumed to be benign or dismissed as cosmetic.

When caught early, treatment is usually surgical — wide local excision with appropriate margins. But because of its rare location, delayed diagnosis is not uncommon, and nodal involvement may be more likely by the time it’s addressed. Importantly, this is still considered a skin cancer, not a breast cancer, and doesn’t respond to therapies typically used for ductal or lobular breast carcinomas.

Why It’s Clinically Important to Separate the Two

A lump in the breast raises alarm — and in someone with a melanoma history, it can mean very different things depending on the origin. If it’s a new primary breast tumor, the workup may lead to mammography, core biopsy, and a path toward surgery, radiation, or endocrine therapy. If it’s melanoma masquerading as a breast mass, the focus shifts to systemic staging and immunotherapy.

For clinicians, the key is suspicion. For patients, it’s awareness. If you’ve had melanoma before and notice any new mass — even one that seems unrelated to the skin — it’s worth investigating. Not because it’s likely, but because when it happens, the implications are significant.

Part Six: Hormones, Immunity, and the Microenvironment

Sometimes two cancers arise in the same person because of a shared genetic mutation. Other times, the connection is less direct — shaped not by inherited DNA, but by what the body’s environment allows. Hormones, immune surveillance, chronic inflammation, and local tissue signals all shape how tumors form, grow, and spread. In the case of melanoma and breast cancer, these subtle, system-wide influences may help explain why the two sometimes appear in tandem — even when no gene mutation is found.

Estrogen’s Unclear but Persistent Role

Most people think of estrogen in the context of breast cancer. It fuels many types of breast tumors, especially those classified as ER-positive, and plays a central role in risk, treatment, and prognosis. But estrogen doesn’t act only on the breast. It affects skin, melanocytes, and immune cells, too.

Some studies have found that estrogen receptors — particularly ER-β — are expressed in melanoma cells, though less consistently than in breast tissue. The presence of these receptors suggests that hormonal signaling could influence melanoma progression, especially in premenopausal women or those undergoing hormone therapy. However, findings have been mixed, and no direct causality has been established. It’s still unclear whether estrogen actively drives melanoma growth, protects against it, or simply coexists as a background variable.

The hormonal therapies used in breast cancer treatment — like tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors — can shift systemic hormone levels significantly. Whether these changes influence melanoma risk later is still speculative, but the idea has prompted ongoing research into how endocrine modulation affects second cancer development.

Immune Surveillance and Checkpoint Dysregulation

Another place where breast cancer and melanoma may intersect is through immune regulation — particularly in the context of immune checkpoint activity.

Melanoma is one of the most immunogenic solid tumors. It often responds to immunotherapies like checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4), and many of its mutations produce antigens recognizable to T cells. Breast cancer, while less overtly immune-driven, also involves significant immune signaling — especially in triple-negative or HER2-positive subtypes, where tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes often correlate with prognosis.

The immune system acts as a gatekeeper, detecting and eliminating early tumor cells before they gain traction. But once that surveillance is compromised — whether by chronic inflammation, regulatory T-cell activation, or simply the wear-and-tear of cancer treatment — the body becomes more permissive to second malignancies. In that sense, having one cancer may not just be a biological coincidence, but a sign that something deeper has shifted in how the body patrols its own boundaries.

The Tissue Microenvironment: Fertile Ground for New Growth

Every cancer arises not just from genetic mutations, but from the environment it grows in — a complex mix of immune cells, fibroblasts, blood vessels, hormones, and extracellular signals. That environment is shaped by age, lifestyle, prior disease, and treatment history. A person who’s undergone chemotherapy, radiation, or hormonal suppression doesn’t just carry scars — they carry altered biochemistry, in ways science is still trying to map.

There’s a growing awareness that the long-term effects of cancer treatment — especially immune disruption and hormonal shifts — may change the “soil” in which other cancers can grow. This doesn’t mean breast cancer causes melanoma, or that melanoma sets the stage for breast tumors. But it does mean that shared biological vulnerabilities — amplified by prior illness or treatment — might make some patients more susceptible to developing both.

There is no single pathway that links breast cancer and melanoma. But the intersection of hormonal signaling, immune control, and tissue readiness offers a compelling framework — not to prove causality, but to understand how these two diseases might find similar ways in.

Part Seven: Screening, Surveillance, and Survivorship

After a cancer diagnosis, the rhythm of care changes. There’s treatment, of course — surgery, medication, radiation, recovery — but then comes the long tail of surveillance. Follow-up visits. Imaging. Blood tests. The ongoing, cautious watching that becomes a part of life after cancer.

For survivors of either breast cancer or melanoma, that surveillance usually stays within familiar lines: mammograms for the breast, skin checks for the skin. But when both cancers are on the table — whether in one patient or across a family — the lines start to blur. The question becomes: Does having had one of these cancers change how we screen for the other?

For Melanoma Survivors: Should Breast Cancer Screening Change?

In most cases, breast cancer screening for melanoma survivors follows standard population guidelines. That means routine mammograms starting around age 40–50, depending on national recommendations and personal risk. But if a melanoma survivor has additional risk factors — a family history of breast cancer, a known genetic mutation, or prior chest radiation — screening may begin earlier or be done more frequently.

Some dermatologists and oncologists have also started encouraging more comprehensive risk assessments for long-term melanoma survivors, especially women under 50 or those with multiple atypical moles. In these cases, even without a known genetic syndrome, there may be enough concern to justify referral for breast cancer risk evaluation, which could include enhanced imaging (like MRI) or consultation with a breast specialist.

For Breast Cancer Survivors: Is Skin Surveillance Necessary?

Melanoma doesn’t appear on most breast cancer survivorship plans. But maybe it should — at least for certain patients. While there are no formal guidelines recommending skin exams after breast cancer, many cancer centers now routinely include dermatology referrals in the follow-up care of patients with elevated skin cancer risk. That includes those with:

- Fair skin and a history of sunburns

- Multiple dysplastic nevi (atypical moles)

- Prior radiation to the chest wall

- Family history of melanoma

In these cases, a full-body skin exam once a year can offer real peace of mind — and in some cases, early detection of a melanoma that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Survivorship Means More Than Watching for Recurrence

Too often, surveillance focuses only on one thing: Is the first cancer coming back? But survivorship is broader than recurrence. It includes the possibility — however small — of second primary cancers, especially when the body’s internal landscape has been changed by disease, treatment, or time.

For patients who’ve had breast cancer and melanoma — or who carry known risk markers for both — long-term follow-up needs to stretch wider. That may mean seeing both a dermatologist and a breast specialist regularly. It may mean discussing genetic testing, even if one test was already done. And it certainly means that both cancers — not just the first — should be part of the ongoing conversation.

Surveillance shouldn’t mean living in fear. But it should mean staying in view — maintaining just enough watchfulness to catch what matters, without being consumed by what might happen. And in people with histories of both breast and skin cancers, that balance starts with recognizing the link, then folding it gently into care.

Part Eight: Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the link between breast cancer and melanoma?

Breast cancer and melanoma are biologically different diseases, but they do appear together more often than chance alone would predict. The link isn’t direct — one doesn’t cause the other — but certain factors may increase risk for both. These include shared genetic mutations like CDKN2A or BRCA2, overlapping hormonal or immune system influences, and possible effects from cancer treatments such as radiation or immunosuppression. Survivors of one often undergo closer medical monitoring, which may also increase the detection of the second. So while they aren’t typically considered part of the same syndrome, the connection is real enough that many oncologists now factor it into follow-up care.

Does melanoma increase the risk of breast cancer?

Yes, though modestly. Studies have shown that women who survive melanoma — especially those diagnosed before age 50 — face a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer later in life. The reasons aren’t fully understood, but genetic predisposition plays a likely role. In some cases, the overlap may be tied to underlying mutations that affect both DNA repair and cell-cycle regulation. Increased screening after a melanoma diagnosis may also contribute to earlier detection of breast cancer, though this doesn’t account for the entire increase. The risk is not high enough to change breast cancer screening guidelines for everyone, but it may justify more personalized surveillance in certain patients.

Can melanoma spread to the breast?

It can, but it’s rare. Melanoma is an aggressive cancer that can metastasize to almost any organ, including the breast, though the breast is not a common site of spread. When it does occur, it usually presents as a painless lump, and is often initially mistaken for primary breast cancer. A biopsy is required to determine whether the mass is actually a melanoma metastasis. In these cases, treatment follows melanoma protocols, focusing on systemic therapy rather than breast cancer–specific approaches like hormonal treatment. Melanoma in the breast generally signals advanced disease, and requires full-body imaging to assess for other sites of spread.

Are people with breast cancer more likely to get skin cancer?

Some are, especially those with certain genetic backgrounds or who have received radiation therapy. A history of breast cancer doesn’t automatically mean a person will get melanoma, but long-term survivors — particularly those treated at a younger age — do show a slightly elevated risk in some population studies. The risk appears to be more pronounced in patients with light skin, multiple moles, or family histories of melanoma. For these individuals, annual skin checks may be reasonable as part of routine survivorship care, though formal guidelines haven’t yet been universally adopted.

Should survivors of one be screened for the other?

It depends on the full clinical picture. If someone has had breast cancer and has additional skin cancer risk factors — such as fair skin, prior chest radiation, or a family history of melanoma — then a yearly dermatologic exam is a prudent step. Likewise, if someone has had melanoma and also has a family history of breast cancer, or other indicators of elevated risk (like early-onset diagnosis), enhanced breast screening or genetic counseling may be warranted. There’s no one-size-fits-all rule, but when two distinct cancers overlap in a patient or family, screening should be tailored, not routine.

Closing Thoughts

There’s no single mechanism that ties breast cancer and melanoma together — no common cause, no simple genetic switch. But the overlap is real. Sometimes it’s driven by shared biology, sometimes by inherited mutations, and sometimes by the long reach of cancer treatments that change how the body responds to new threats. For some patients, the link is written into their genes. For others, it’s a matter of vigilance, early detection, or plain statistical chance.

What matters is not just recognizing that these two cancers can co-occur — it’s understanding what to do when they do. That means knowing when to screen more carefully. When to refer for genetics. When to expand the scope of survivorship care. And when to stop treating cancers as isolated events and start seeing them as part of a broader risk landscape.

Whether you’ve had breast cancer, melanoma, or both — or are simply trying to understand how they might relate — the goal isn’t to worry more. It’s to think more clearly, act more deliberately, and keep the conversation going between specialties that haven’t always overlapped.